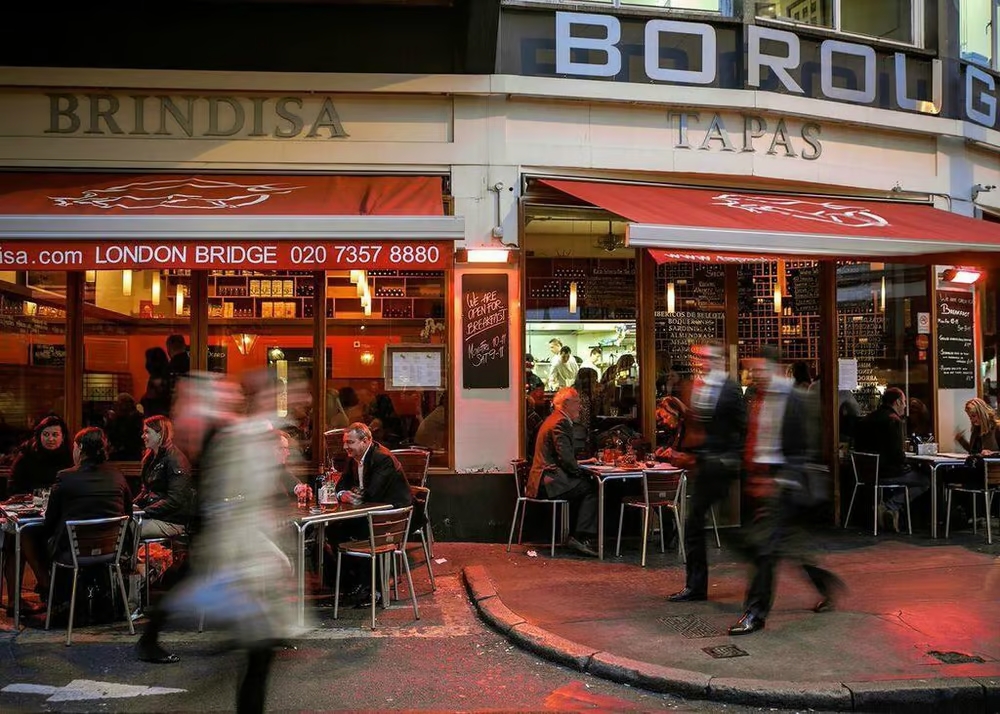

Brindisa Tapas bars have just celebrated their 25th anniversary. Harden’s caught up with founder Monika Linton

HARDEN’S: Monika, many congratulations on the first quarter century of Brindisa Tapas – but the bars are just the tip of the iceberg, the most visible aspect of the import company you set up in 1988 to import Spanish food. What was your background before that – and what made you set up the company?

MONIKA: It all started from learning Spanish at school. It wasn’t my first foreign language, but I really enjoyed it and ended up studying Spanish at university. I had a holiday job working in a restaurant on the Costa Brava and spent my year out studying in Peru. Then when I graduated I wanted to consolidate my Spanish, so I taught English in Catalonia for three years.

I lived in the countryside, getting by in a mixture of Spanish and Catalan, and gained real experience of the rural economy there. Logistics in Spain were not very developed then, so you didn’t get products from Andalucia at the other end of the country in Catalonia, for instance – but that meant the food culture was very local. People learned about ingredients and tastes at home, and really understood that good food is made by craftspeople on a small scale – unlike in Britain, where we simply expect food to be cheap.

Spain didn’t join the EU until 1986, so very little Spanish food left the country. The British had been holidaying on the Costas, and had discovered sangria and paella – but there was very little knowledge of the food of the interior. I didn’t want to teach forever, so I came back to London and started looking at ways of importing some of the Spanish ingredients that I had come across. My brother was fed up with his job in City, so headed in the other direction to Barcelona, so we started working together.

With a business like Brindisa which is so early into a new market it can be difficult to tell which came first: did you sense a growing demand and fulfil, or did you create a market? Perhaps it is not a question of either/or!

I was pretty much the first person to import many of these products to Britain – and London was also key to generating international interest, from the US and Australia as well as other European countries. The Spanish realised they could use London as a test run for exports, and I worked closely with the Spanish Embassy.

And yes, we were very lucky with the timing. The Barcelona Olympics and the Seville World Expo in 1992 increased interest in Spain, and supermarkets like Safeways began stocking Spanish products.

We also managed to get the products into the ‘top shops’, which stimulated demand – Harrods and Fortnum’s were really important then, stocking products such as Ortiz tuna. And there was a brilliant generation of intellectual, adventurous British chefs who wanted to source the best products for their kitchens: people like Alastair Little, Simon Hopkinson and Mark Hix. We got to know them literally by the back door – selling cheeses from the back of a van, which we would drive to the restaurants and the chef would take his pick.

The process has continued, with Spanish chefs like Jose Pizarro and Nieves Barragan bringing top-quality Spanish cooking to a wider audience. Chefs also help by highlighting specific regional products on their menus, so people are now familiar with Cantabrian anchovies, judion beans and padron or piquillo peppers – I remember when Mark Hix listed just “piqillo” on a menu, trusting guests to know it was a pepper.

It’s not always an easy process. We have been pushing tinned fish for 35 years, sometimes expanding and sometimes contracting the range. But it seems the penny is dropping now, with more people understanding that canned fish can be a fantastic, high-quality product.

Brindisa has also played a central role in another key development on the London food scene – the transformation of Borough Market from a fading traditional wholesale market into a magnet for food-loving consumers, and more recently into a restaurant hub. How did this come about?

The market is owned by diocese [Southwark Cathedral is next door], which is why the site has never been exploited for housing or offices. We had our warehouse next door in Winchester Walk, and along with Neal’s Yard cheeses in particular we were trying to persuade the trustees who represent the interests of the diocese to move with the times – they were losing wholesale traders at the time so did really need a new income stream. Over 30 years it has developed into a market where the ethic is quality and craft. And it’s always changing – there needs to be a good balance, so it doesn’t just become a street-food market.

Other imported dining cultures (French, Italian, Chinese, Japanese for instance) have tended towards a certain level of formality, with waiters, tablecloths and so on. Tapas has reversed this, making good dining far more casual, with the idea that you could sit at a bar in your jeans at any time of the day and order snacks cooked with as much care as a dish in a smart restaurant. This has now spread from Hispanic to other cuisines, so restaurants happily describe themselves as British, Italian, Japanese or Vietnamese ‘tapas’ – and we know just what they mean. What do you think of this development?

Well, with my background it does sound a bit odd to me when people talk of British or whatever tapas. But I think Spain should be proud of the way the world has embraced the term and the attitude. And I think it is great that people can enjoy a moderately affordable plate and a glass of wine with that feeling of a treat – it doesn’t have to be a full-blown sit-down meal.

Any business based on imports clearly requires good international trading conditions. Brexit must have been a nightmare for Brindisa. There’s also the associated problem of recruiting kitchen and service staff who know about Spanish food. How have you coped?

Yes, it seems we have come a strange full circle since the business started, from Spain joining the EU and the UK leaving. So importing has certainly become more expensive, and finding staff is now really difficult – we have had to make sure our training programme is much stronger when recruiting people without Spanish heritage.

As we enter the New Year, we look to the future. So what is next for Spanish food – and for food as a whole – in the UK? Or have we reached peak tapas?

Well, of course I’m going to say No to that! But I think there a lot of areas with potential, particularly in vegetarian ingredients – both from Spain and in general. For a start, there are all sorts of pulses where we can track down the best varieties, regions and producers. This is something I have researched a lot.

The same goes for varieties of rice with particular qualities, with varieties of tomatoes or potatoes and many other vegetables, and also citrus fruits. This extends beyond Spain to countries like Greece, where herbs like oregano and thyme grown in the sun pack highly concentrated flavour.

From Spain, there are still many levels of quality of olive oil or vinegar that are not widely known, and people are beginning to realise that it is worth paying a premium for the best. Spain also has all sorts of nuts, including almonds and chestnuts, and then there are ingredients from Spain that are more famous from other countries. Italian truffles and French foie gras are prized around the world, but Spain produces its own high-quality versions that are much less expensive.

Cured dried fish is another example – baccala, Spanish salt cod, still hasn’t had its day here. So there is plenty more for us to do, and for the public to discover.

Finally Monika, any recommendations?

Maya’s Bakehouse, near where I live in Brixton. It’s tiny, sells out every day, and is a fantastic example of an independent artisan food business – ‘small is beautiful’!